The Life and Legacy of Sam Shepard

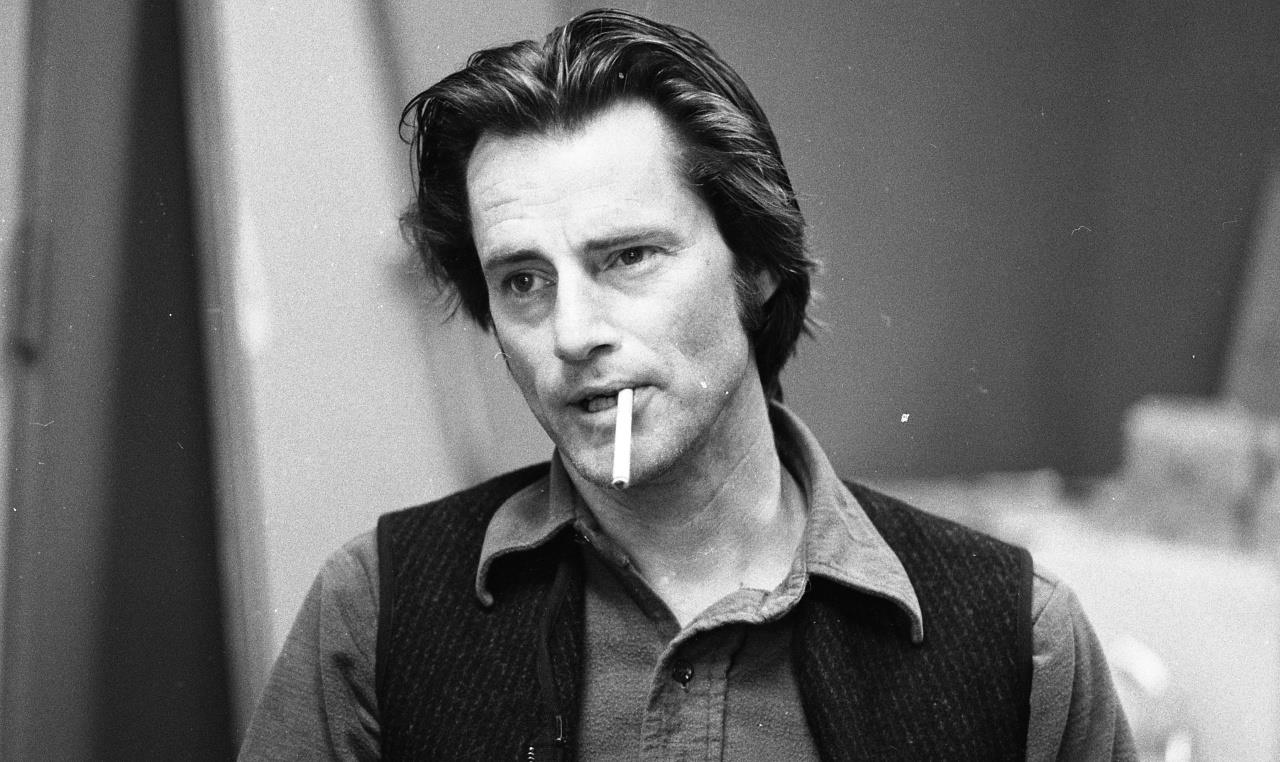

In 1983, Sam Shepard was at the peak of his creative powers. He had already earned a Pulitzer Prize for his play “Buried Child” (1978), and his latest work, “Fool for Love,” which premiered in February at the Magic Theatre in San Francisco, would become his longest-running show when it moved to New York in May. Later that year, he portrayed Chuck Yeager in the film adaptation of “The Right Stuff,” earning an Oscar nomination and introducing him to a level of stardom rarely achieved by American playwrights. However, there was an underlying challenge. David Thomson noted in a 1983 issue of Film Comment that Shepard had a strong aversion to being liked, and while he might not provoke antagonism, he would not tolerate the softness of amiability.

This reticence kept Shepard from becoming a great actor but allowed him to be a trusted one. His iconic beauty, with imperfections like crooked teeth, only added to his allure. A rock ’n’ roll Gary Cooper, his wariness extended beyond acting. From a 1981 journal entry: “This is for you ‘archivists’ who snoop into other people’s lives… hoping to solve some mystery or other about yourselves through others: YOU’LL NEVER FIND IT HERE!!”

What is inarguable is that Shepard left behind a wealth of material, including 56 plays and seven books of prose and poetry. His private journals and correspondence also offer insight into his life, making them irresistible for biographers. Robert M. Dowling, in his book “Coyote” (Scribner, 480 pages, $31), presents the most complete portrait of Shepard’s life to date. This is the third Shepard biography in the past decade, and Dowling, a professor of English at Central Connecticut State University and co-editor of “Conversations With Sam Shepard” (2021), uses journal entries and family correspondences to provide intimate shadings on a story familiar to fans of literary biography or those who have attended a 12-step recovery program.

Early Life and Influences

Sam Shepard Rogers grew up east of Pasadena, California. His father, Sam Rogers, flew 46 B-24 bomber missions during World War II and struggled to adjust to postwar life as a high-school Spanish and Latin teacher. His intelligence and talents were eventually derailed by alcoholism. “One thing that I’ll always be eternally grateful to him for… is he introduced me to García Lorca when I was a kid,” his son later said. “In Spanish no less.”

The elder Rogers ruled his home with fear and discipline, physically pummeling his son. “His life was like a time bomb waiting to explode,” his wife, Jane, recalled. He also insinuated that his son was less than a man, a trauma that might explain Shepard’s stoic cowboy persona as well as his fear that his father was right. The old man became a menacing force behind many of Shepard’s plays.

Young Sam found refuge in farm life. “My greatest ambition was to be a veterinarian at the Santa Anita racetrack,” he wrote in a notebook. Instead of life as a farmer, he cast himself as Sam Shepard and fled home as soon as he could.

Career and Personal Life

He arrived in New York City in the early 1960s, and by the age of 20, he drew attention to his plays, a riot of percussive energy. As Edward Albee put it, “what Shepard’s plays are about is a great deal less interesting than how they are about it.”

Shepard wrote prolifically and found himself with many white-hot irons in the American fire. When Michelangelo Antonioni sought a hip, young voice to write the script for “Zabriskie Point” (1970), he turned to Shepard, who also worked on (ultimately unpublished) projects for the Rolling Stones and Robert Redford.

His romantic life was rarely dull. In 1969, he married O-Lan Jones, whom he met through the theater. By 1970, he was involved in an affair with Patti Smith, who would remain a lifelong friend (he encouraged her to set her words to music). He was also romantically linked to Joni Mitchell, whom he met during the filming of Bob Dylan’s 1978 concert film, “Renaldo and Clara.” (Shepard was the subject of Ms. Mitchell’s 1976 song, “Coyote.”) Shepard would leave Ms. Jones for Jessica Lange, his co-star in the 1982 film “Frances.” Their love triangle would play out, in part, in “Fool for Love.”

Literary Achievements and Personal Reflections

Shepard won 10 Obie Awards. His crowning achievement, the cycle of family plays—“The Curse of the Starving Class” (1977), “Buried Child” (1978), “True West” (1980), “Fool for Love” (1983), and “A Lie of the Mind” (1985)—place him on a continuum of great American playwrights going back to Eugene O’Neill.

Mr. Dowling is a discerning and sympathetic, if occasionally starchy, guide through Shepard’s oeuvre. The connections to O’Neill and Samuel Beckett, in particular, ring true. He quotes Stephen Rea, the Irish actor, who wrote that Shepard’s plays, “more than any since Beckett’s, feel like musical experiences.” When Shepard died, a copy of Beckett’s “Endgame” rested on his bedside table.

Shepard viewed his own obsessions—womanizing, booze, writing—with a foreboding sense of the inevitable. “The frantic futility of constantly searching for a new place,” he wrote his longtime friend, Johnny Dark, “a new life, a new partner. As though change itself were some kind of elixir.” In 2011, after his breakup with Ms. Lange, he wrote: “My myriad girlfriends are all somehow disappointing. My only solace seems to be writing.”

Personal Habits and Philosophy

Acting helped him afford horses, and he was a skilled equestrian. Here was a man who’d rather ride a horse than drive a car, and who would rather drive a car—or pickup truck—than fly in a plane. A natural man who most enjoyed spending his day outside. What fueled the words and the life remains tied to the desire for family and the reflex to run—an exile.

In “Coyote,” Mr. Dowling doesn’t interview Ms. Lange, or Shepard’s children, or Ms. Jones, who tells him that she is working on her own memoir. So while this volume digs deeper still into the mind and adventures of the playwright, eight years gone, you get the sense that there’s more to come—more clues to that elixir that sent a boy packing and the man looking forever for home.

Mr. Belth is the author of the Substack newsletter “Dig This With Alex Belth.”