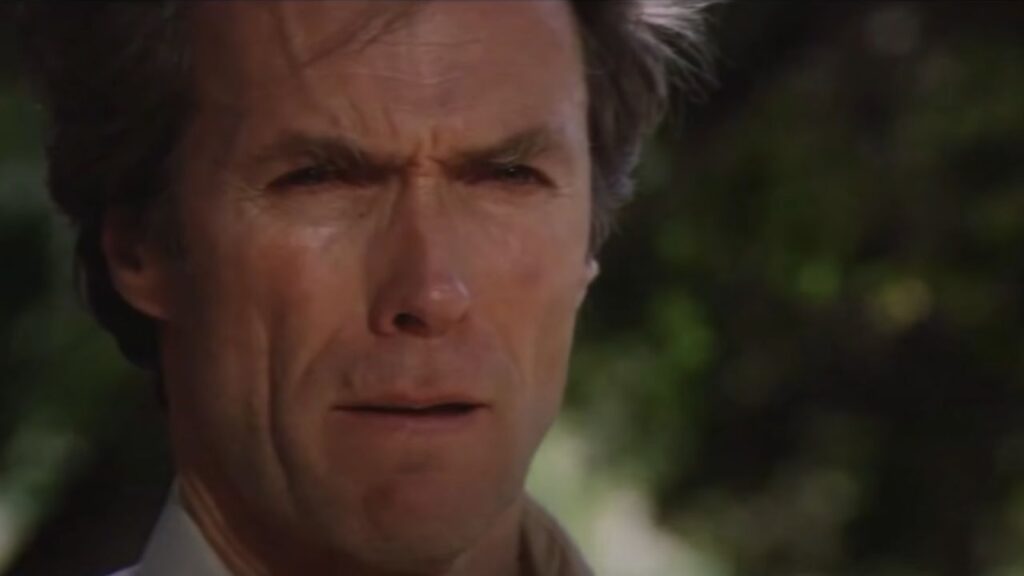

Clint Eastwood: Beyond the Gun and the Scowl

If you only know Clint Eastwood from a .44 Magnum and a scowl, you probably assume you already know his politics. However, on the Facts Verse podcast, host Tim Blane and film critic and biographer Shawn Levy spend almost an hour explaining why that knee-jerk assumption is mostly wrong — or at least wildly oversimplified.

Levy, who literally wrote the book on Eastwood, walks through what the actor-director has actually said and done on gun control and politics, while Blane pushes him to connect that to iconic characters like Dirty Harry. The picture that emerges is way messier, and honestly, a lot more interesting.

Dirty Harry As A Warning, Not A Role Model

Shawn Levy starts right where everyone’s brain goes first: Dirty Harry and The Man with No Name. He tells Tim Blane that these aren’t cool fantasy heroes you’d want to trade lives with. In Levy’s words, they’re “damaged guys,” men at the “tip of the spear” who do ugly things and then go home alone to live with what they’ve done.

Levy stresses that while the Dirty Harry films definitely have a “pro-violence / authoritarian tenor,” the movies themselves aren’t simple cop worship. He points out that the second film is literally about a squad of vigilante officers murdering people they think the justice system failed, and Harry Callahan ends up going after them. That was deliberate, Levy says. Clint Eastwood as producer positioned characters to “the right of Harry,” so the audience could see a darker version of the fantasy and watch Harry push back against it. It’s a nuance a lot of people miss when they only remember the one-liners and the gun.

“Dirty Harry Was Absurd” – And Clint Knew It

Levy also tells Blane that Eastwood eventually saw how over-the-top the franchise had become. He notes that the later Dirty Harry movies slide into almost cartoon territory. By the final film, Harry is being chased around San Francisco by a toy car with a bomb in it. Levy calls that progression “absurd,” and suggests Eastwood knew it too.

According to Levy, the shift into movies like Every Which Way But Loose and Any Which Way You Can – the famous orangutan comedies – was partly Eastwood trying to escape the Dirty Harry box. Levy jokes that Eastwood “settled into his role as America’s goofball,” and that the success of those films gave him another franchise so he wouldn’t have to keep making Harry sequels. That alone cuts against the idea that Eastwood is obsessed with being the permanently armed, grim avenger. At some point, even he seemed to treat Harry more like a costume he could hang up than a template for real life.

Eastwood Backed Handgun Control – While Owning Guns

The biggest surprise for a lot of listeners will probably be Eastwood’s record on gun policy. Levy tells Tim Blane that Eastwood supported the Brady Bill for handgun control and signed petitions calling for handgun regulation after the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy. That’s a matter of public record, Levy says, and it doesn’t fit the easy “Hollywood gun nut” stereotype people glue onto him because of his characters.

At the same time, Levy makes it clear Eastwood is not anti-gun. He says Eastwood has owned firearms, and in the 1980s, when he was one of the most famous actors on the planet and an elected official, he held a concealed carry permit because he and his family were getting death threats. Levy adds that he doesn’t believe Eastwood keeps handguns today, but still has “scatter guns” – shotguns and similar long guns – on his large property in Northern California. He frames that as “responsible husbandry of the land,” not some kind of “blood lust.”

That combination – supporting handgun restrictions, using a carry permit when there were real threats, and keeping working guns on rural land – looks a lot more like a practical, situational view than a rigid ideological one.

Not Your Standard Right-Wing “Darling”

Tim Blane pushes Levy on the broader politics: if you only see the tough-guy roles and the 2012 Republican National Convention speech, you might assume Eastwood is just a right-wing mascot. Levy pushes back hard on that. He tells Blane that, over the decades, Eastwood has supported abortion rights, civil rights, women’s rights, and environmental causes – positions not typically associated with the modern right.

Levy describes him as a “lifelong conservationist” and animal lover, noting that his eldest daughter Allison is active in the animal-rights world and that the Eastwood family name appears on related foundations. Politically, Levy says Eastwood has usually voted Republican but is better described as libertarian than party-line conservative. He notes that Eastwood has also donated to Democrats and often comes back to one basic mantra: independence.

Tim Blane ties that theme to Eastwood’s characters – the lone man who wants to be left alone, who insists on making his own decisions. Levy agrees, pointing to The Outlaw Josey Wales, where the character briefly assembles a kind of found family, then rides off rather than settle into a neat social role. That, Levy suggests, is very close to Eastwood’s own internal compass: build something, fix something, then get out of the way.

The Empty Chair And The Improv Gone Weird

Blane and Levy also revisit the moment that turned Eastwood into a meme: the 2012 Republican National Convention speech with the empty chair “standing in” for Barack Obama.

Levy admits that when he watched it live, his “hair was on fire,” just like many of his left-leaning friends. People were furious and frankly embarrassed. But he tells Blane that, rewatching it later, and hearing his actress partner’s take, it plays more like an improv exercise gone sideways than some grand, sinister statement.

According to Levy, Eastwood basically walked onstage with no script. He saw the chair, grabbed it, and started riffing like an actor doing an empty-chair scene in a workshop. It was so strange that, as Levy recalls, even Fox News commentators floated the idea that Eastwood might have been a secret Hollywood lefty trying to sabotage Mitt Romney. Levy says Eastwood himself later blamed the Romney campaign for not asking, “By the way, what are you going to say?” beforehand. His main “argument” for Romney, Levy notes, was simply: “He’s a businessman” — which, to Eastwood, is praise, but hardly a full-blown ideological manifesto.

Mayor Clint: Ice Cream Cones, Sidewalks, And Zoning

One of the most telling parts of the conversation is when Tim Blane asks about Eastwood’s brief stint in actual politics. Levy explains that Eastwood became mayor of Carmel, California, not because he had grand ambitions, but because he was mad about zoning. Eastwood owned property and couldn’t get a land-use change approved to build a simple two-story office building.

At the time, Levy says, Carmel was so “tradition-bound” that wanting that small change made him look like a radical. The town had no downtown sidewalks, technically banned high heels, and didn’t even use street numbers on houses, which forced residents to rely on P.O. boxes because the Postal Service couldn’t deliver to “the pink house on Drury Lane.”

As mayor, Levy says, Eastwood legalized basic things like ice cream cones to-go, built stairs from the main sidewalk down to the beach, and pushed for modest land-use reforms to give local business a little more freedom. Once those changes were done, he was done. No run for governor. No presidential campaign. Just two years of “fix this and let me get back to my day job.”

A Republican Who Fought Toll Roads Through Parks

Levy adds another example that complicates the usual labels: Eastwood’s service on the California State Parks and Recreation Commission. He explains to Blane that Democrat Gray Davis appointed Eastwood, and when Arnold Schwarzenegger replaced Davis as governor, he kept Eastwood on. The two men were friendly, skied together, and generally got along. But Levy says Schwarzenegger ultimately let Eastwood go after Eastwood opposed building toll roads through state parks. Eastwood’s attitude, as Levy paraphrases it, was simple: “You don’t hire me to a parks commission and then ask me to run a highway through a park.”

Schwarzenegger is hardly a hard-right figure, Levy notes, yet on that issue he was to the right of Eastwood. Again, the picture you get is not of a straight-ticket conservative crusading to pave everything, but of a stubbornly independent guy protecting open land even when it meant breaking with his own party’s governor.

A Man, Not A Meme

By the end of the conversation, Tim Blane and Shawn Levy have quietly dismantled the idea that Clint Eastwood can be summed up by a movie poster and a few memes. Levy keeps coming back to the same idea: Eastwood is a man whose art, personal life, and politics overlap, but don’t line up in a simple way.

He supported handgun control and also carried when his family was threatened. He played ultra-violent cops and then drifted into orangutan comedies. He backed civil rights and conservation but gave a convention speech for a Republican nominee.

From my perspective, the most useful thing Blane and Levy do is insist on context. They focus on what Eastwood actually said, signed, and did, instead of treating Dirty Harry as a documentary. It’s a reminder that celebrity politics is always more complicated than cable-news shorthand – and that even the guy with the big gun and the bigger squint might be thinking a lot more deeply about independence, responsibility, and limits than the caricature suggests.